Multithreading in C++: Producing and Consuming PI

September 2022 (4243 Words, 24 Minutes)

Promotional picture for a pie eating contest

Promotional picture for a pie eating contest

Hi, I’m Oleg, a Junior Game Audio Programmer and this is a continuation to my previous blogpost on multithreading. In the last post, I’ve shown you how to kick off threads and asynchronous tasks without getting into the details of memory sharing. Well, now’s the time to get aquaited with the spooky side of multithreading!

In this blogpost, I’ll introduce you to the concepts and challenges of resource sharing in a multithreaded program and show you the basic C++11 facilities that are commonly used for writing portable multithreaded programs.

By the end of this blogpost, you’ll hopefuly understand the bare minimum required to write multithreaded applications and will have a good list of learning references you can explore to learn more.

Note that in this blogpost, I will not focus on the hardware details relating to multithreading, but I encourage you to read on the subject since all of the constraints present when solving multithreading challenges come from the hardware. Once again, I recommend Jason Gregory’s “Game Engine Architecture” for this.

Credits

Before going any further, let me credit the people, software and learning resources I’ve used in the making of this blogpost:

The practical project / exersice I’ve put at your disposition could not have been possible without the following, in no particular order:

- Visual Studio 2022 (windows) and VSCode (linux)

- Git and Github

- CMake

- Sergey Yagovstev’s easy_profiler

- Fabrice Bellard’s implementation of the Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe formula for generating digits of PI

Although not all explicitly mentioned in the content of this blogpost, the following learning resources were very useful in the making of this blogpost and I encourage you to read / watch them yourself:

- www.modernescpp.com’s explanation of Condition Variables

- My personal bible: “Game Engine Architecture” by Jason Gregory. Most of the information presented in this blogpost can be found in more extensive details in that book alongside a slew of detailed explanations of other topics.

- XXI SINFO - Jason Gregory - Dogged Determination a talk by Jason Gregory on many low-level topics.

This blogpost uses various images, the sources of which have been marked below them as a hyperlink. Care has been taken to use the images in accordance with the creator’s wishes whenever such information has been made available.

Finally, please keep in mind that I am by no means an expert on the subject, and if you spot mistakes or think that some parts of this blogpost need to be adjusted, don’t hesitate to contact me at loshkin.oleg.95@gmail.com.

Sharing Things

“Sharing is caring”, generated with Imageflip Meme Generator

“Sharing is caring”, generated with Imageflip Meme Generator

So far, multithreading has been presented to you in a very friendly manner: define a procedure, kick it off and magic!, everything works! This was true so far unfortunately only because, so far, we didn’t have to worry about sharing resources between multiple threads.

In our previous example of approximating PI using a Monte Carlo method, all that was needed was to generate a bunch of unrelated 2D points asynchronously and count how many of these landed inside the unit circle, an operation that could be split in a set of sub-operations that didn’t need to communicate with each other at all. But what if these sub-operations share some common counter? Or what if the order of these operations is important (say if it’s non-commutative)?

To explore these challenges, let’s reformulate our initial problem to make it inherently serial (meaning the order of operations is important) : instead of approximating PI, let’s print it out, one digit at a time. Since PI is approximatively 3.141592 (rounded down for our purposes), if we wanted to print out it’s digits sequentially, we would expect something like:

Pi is:

3

1

4

1

5

9

2

Any other permutation of these numbers would be incorrect: we can no longer just kick off 7 threads simultaneously and ask them to print the digits of PI: we have made our problem order-dependant, each digit needs to be printed in the right order.

This also now implies that there needs to be some kind of shared counter that tells each running thread what is the next digit to print and each thread will need to have simultaneous access to it.

Let’s illustrate the issue we will encounter if we’re not careful with a somewhat absurd but representative analogy.

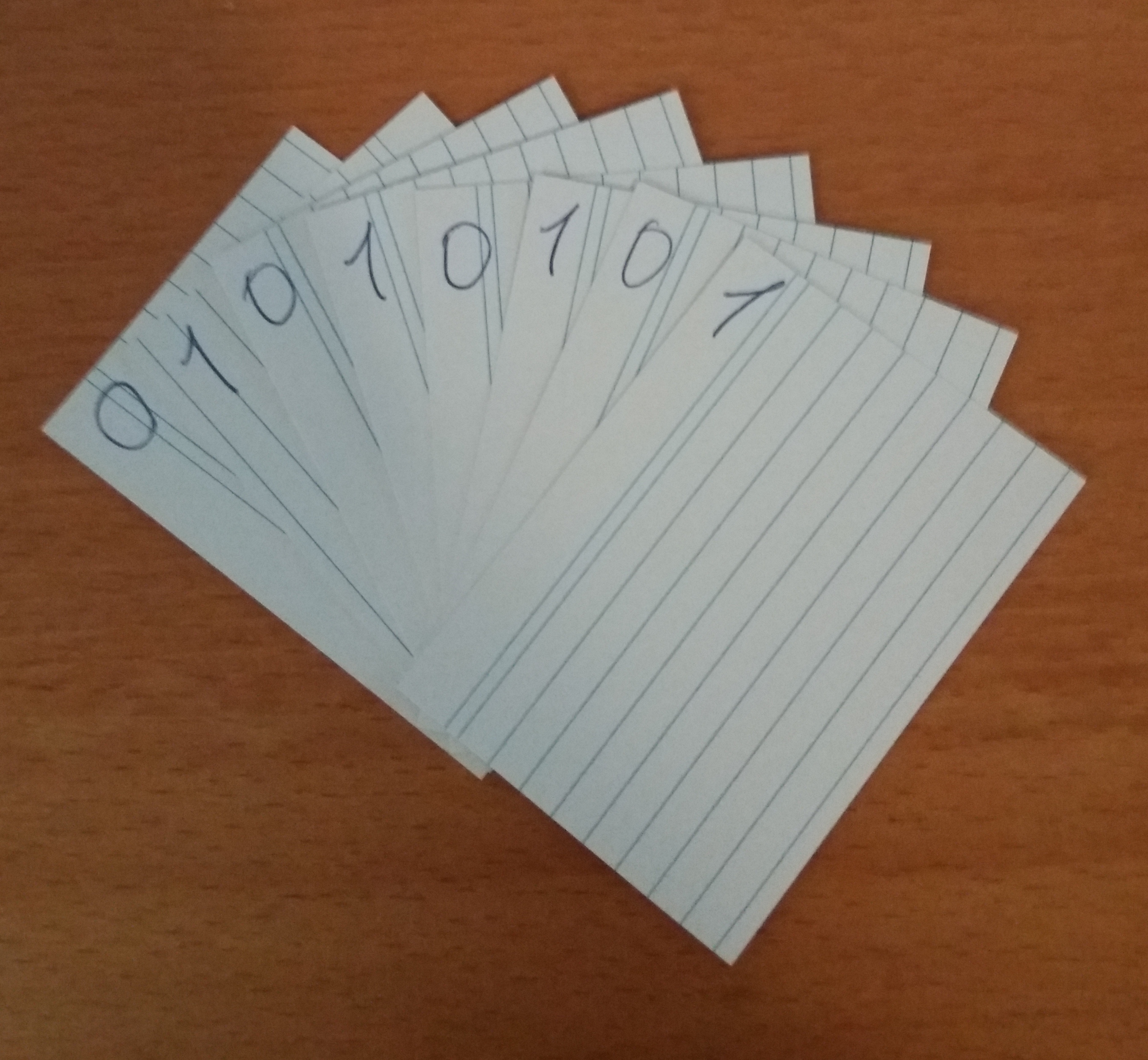

Imagine 7 programmers sitting in a circle, each with a pen in one hand and a little card in the other. At the center of the circle is another small card with the number 0. All the programmers are tasked with incrementing the number on the small card in the middle of the circle by one if the number is 0 or positive or decrementing it if it’s smaller than 0 by writing their result on the card in their hand and putting it on top of the one in the center. What happens next?

In practicality, what we would usually want is for the programmers to take a look at the number on the card in the middle of the circle, write the number that comes after the one they’ve just observed if it’s a 0 and write it on their own little card and set it down in the center on top of the previous one. If each programmer does so in an orderly fashion, we should end up with a stack of 8 cards alternating between 0’s and 1’s, with a 1 at the top of the stack.

In reality of course, the programmers being very dense people and lacking the explicit instruction to wait their turn will simply all simultaneously look at the card in the middle with 0 on it, write 1 on their own cards, and all simultaneously pile up their cards in the middle on top of each other’s in a disorderly fasion. We would therefore end up with a stack of 8 cards with the number 0 at the bottom followed by a bunch of cards with 1’s and 0’s and maybe a few 2’s in the middle from the programmers that got distracted between reading, making a decision and writing.

This somewhat far-fetched analogy is exactly what happens when you’re multithreading in C++ when you don’t take care to instruct these “programmers” properly. You of course understand by now that the programmers in this analogy are threads and the little card in the middle in an address in memory. To be more technical, this is an example of a category of race coditions called a data race.

Getting Things in the Right Order

“Device to Root Out Evil” by artist Dennis Oppenheim

“Device to Root Out Evil” by artist Dennis Oppenheim

As programmers, we were probably taught that our code is executed in the order that we wrote it. I’m sorry but have a harrowing revelation for you: it isn’t.

This might indeed have been the case with early computers but CPU and compiler designers quickly realized that doing things strictly in order leads to the CPU just sitting there and waiting for needed data to arrive from the RAM / lower cache memory. To avoid wasting this computing power, compilers and CPU are allowed to change the order of the execution of the snippets of your code as long as the outcome of this reordering results in an outcome identical to the one obtained had all the instructions been carried out sequentially on a single thread.

And here lies the crux of our headaches: the infrastructure we use has been created for single threaded programs, but with the development of multi-core hardware, we programmers now need to write software that will be ran on an unpredictable physical core (with it’s personal cache memory), and in an unpredictable order! Add to that the fact that modern OS’s use preemption to implement multitasking, and you now also have to take into consideration that any thread that is running can be suddently interrupted by another, potentially one that operates on the very same memory that the one that has just been interrupted, making the current thread’s ongoing computation invalid, and the OS isn’t going to check whether this is the case either!

How are we supposed to make anything work in such conditions? Well, luckily for us, we aren’t left to our own devices (anymore): that’s where multithreading synchronization primitives come into play!

The simplest synchronization primitive is the mutex, first described by Dijkstra. A mutex (short for “mutual exclusion”) is a high-level construct engineered and graciously provided to us mere mortals by the grand wizards that understand the arcane arts of hardware design, compiler design and memory barriers or fences to give us the ability of making an arbitrary operation that shouldn’t be interrupted (a critical section), actually unable to be interrupted (an atomic operation).

While a mutex ensures that critical operations stay atomic, they offer no way for us to order these operations relative to each other. To do that, we need to use a condition variable. A condition variable is a terrible name for the concept of a having a set of threads wait for an arbitrary condition to become true, and when it does, one or all of them waking up and resuming work (perhaps a “thread waiting queue” may have been more descriptive).

Using these two concepts, one can create other more complex multithreading synchronization tools such as the semaphore, which can be implemented as a combination of a mutex, a condition variable and a counter (note that since C++20, there exists the std::counting_semaphore in the C++ language).

Although I will not show how to use it in this blogpost, it can be useful to know of the existance of the std::atomic template as well which can be used in lieu of a mutex for simple data such as integers (commonly referred to as plain old data, POD). As it’s name indicates, any operation on a simple data variable wrapped by this template becomes atomic.

Running the Project

Duckling is affraid to be left behind

Duckling is affraid to be left behind

But that’s enough theory for now, let’s get our hands dirty! First, clone the repository I’ve prepared for you:

https://github.com/LoshkinOleg/Multithreading_In_Cplusplus_Producing_And_Consuming_PI

Note that while this project compiles on Linux, easy_profiler has issues with tracking context switching events on that platform, making the profiler’s use limited for Linux.

If you’re on Windows, just like last time, make an out-of-source build under “/build” using the CMake’s GUI and generate a Visual Studio solution and open it after you’ve ran “moveDlls.bat” to move the dlls in the right place.

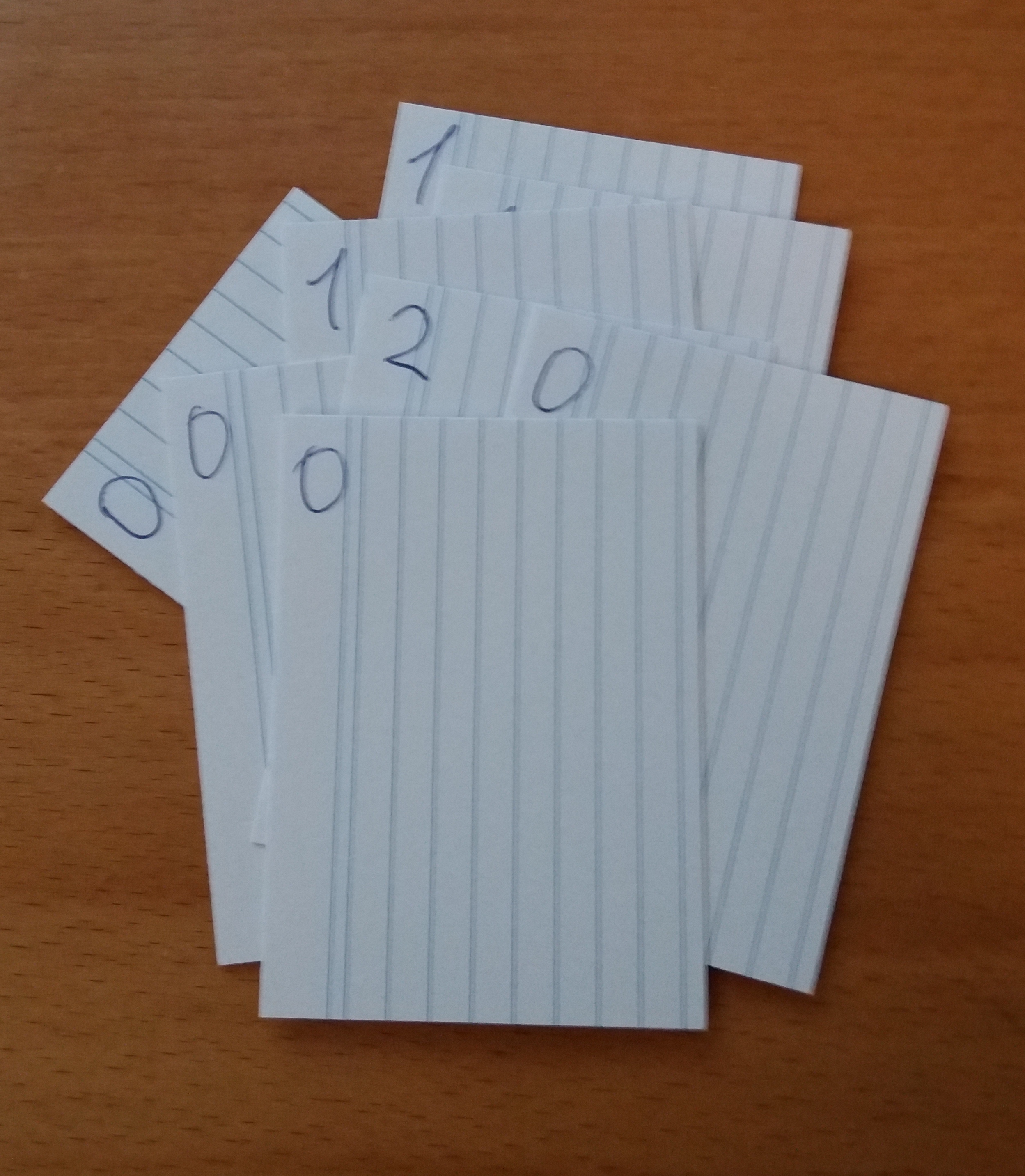

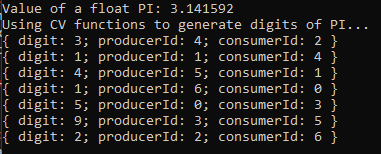

Once you’ve got the project running with the default CMake settings, you should get an output like so:

Let me explain this output real quick. You’ll be implementing four (or three, really, you’ll see) ways to produce and consume individual digits of PI: the “Producer” functions will generate digits of PI at a given position and identify themselves and “Consumer” functions will also identify themselves and append all of this information to a string output. In the last line of the example above for instance, you can see that a Consumer with id “5” has recieved from Producer with id “4” a PI digit of “2” and that this is one output of the “CV functions” implementations.

To make more sense of this, let’s take a look at the contents of the “/Application/src/main.cpp” file. The first lines you should already be familiar with, they define whether to run the implementation that I’ve provided (“/Application/include/workingImplementation.h”) or your own implementation (“/Application/include/exercise.h”). Next is a threads pool and an array defining the indices of the PI digits to Produce:

For 3.14:

First index: 3

Second index: 1

Third index: 4

etc...

Next is a function that will reset all the variables between runs of different producing and consuming approaches. The variables it resets that you don’t see in this current file come from the headers containing the implementations of the functions used in main(). The function just resets variables to their default values and randomizes iterations which defines the order in which the digits of PI will be Produced:

This might seem like an odd way to structure things but you’ll see why we’re doing things this way below: it’s to better demonstrate the properties of std::mutex and std::condition_variable.

Finally comes the main() function, and you’re already familiar with the start and the end of that function: it’s just some easy_profiler code that initializes the profiler and writes the results to disk. In between, you’ve got calls to the functions you’ll be implementing:

For our purposes, we’ll be Producing and Consuming the first 7 digits of PI, but the order in which the threads will be kicked off in will be random to better model what can happen when kicking off threads (thanks to the use of iterations). This is done to emphasize that while some code like this might coincidentally work as expected:

for (size_t i = 0; i <= LAST_DIGIT; i++)

{

threads.push_back(std::thread(NoMutex_Producer, i));

threads.push_back(std::thread(NoMutex_Consumer, i));

}

for (auto& thread : threads)

{

thread.join();

}

It is not guaranteed to work that way. Explicitly shuffling the order of the push_back’s like we’re doing here makes this point more obvious.

Now that you’ve seen how the main logic of the Application works, go ahead and uncheck the USE_WORKING_IMPLEMENTATION define in CMake GUI and let’s take a look at the part of the code you’ll actually be working in which is contained in “/Application/include/exercise.h”:

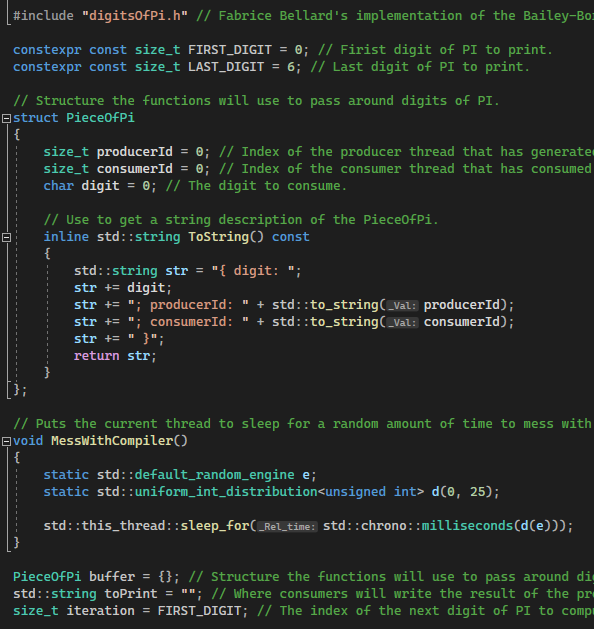

First, the included header “/Application/digitsOfPi.h” contains a modified implementation of Fabrice Bellard’s implementation of the Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe formula used here to compute an arbitrary digit of PI. The details of this implementation are out of the scope of this blogpost (as well as out of my own understanding to be honest) but to summarize it: it’s a very efficient algorithm allowing to compute an arbitrary set of digits of PI without having to compute all the part of PI that comes before the set of digits we’re actually interested in.

Next are some literals if you wish to change the range of PI to compute, I’ve chosen the first 7 digits because they’re the ones we’re most familiar with but the code should work just fine with any other positive values (within the range supported by size_t obviously which is 2^64 on most machines).

The PieceOfPi struct is the data that Producers and Consumers will be passing to each other and it contains fields for the actual digit of PI and two fields allowing identification of the Consumers and Producers involved in a given transaction. It also has a method to get a string representation of the structure to be able to print it.

Next up is the MessWithCompiler function which, as it’s name indicates, makes the code from which it is called from unpredictable both for the compiler and the CPU: it introduces a random delay in the execution that varies between 0 and 25 milliseconds. We’ll be using this function to ensure that our code is capable to withstand unpredictable delays (like that which can be introduced due to preemptive multitasking) and therefore unpredictable relative order of execution of threads.

Finally, we’ve got the first three global variables we’ll be using to implement the regular, non-multithreaded approach of our producer-consumer problem. The buffer variable is the unit of PI that will be passed from Producer to Consumer, one at a time. The toPrint string is where the Consumers will append their results to and iteration will be used to define the next digit of PI to Produce.

Let's Write some Code!

God answering prayers from “Bruce Almighty, 2003”

Alright, enough theory, let’s go to coding stuff! Just like in the previous blogpost, I’ve marked the areas where you should be writing code with descriptive TODO’s, so feel free to attempt all of those things by yourself first and come back to this blogpost if you’re stuck!

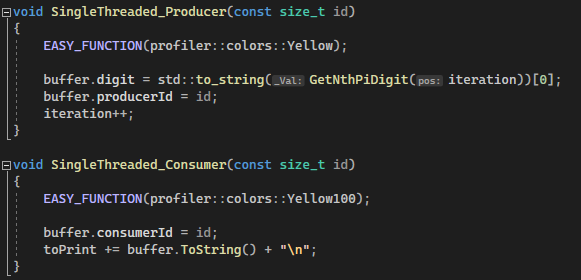

Let’s start with a SingleThreaded, sequential implementation. I doubt you’ll have any trouble implementing this first approach. As a reminder, this is how SingleThreaded_Producer and SingleThreaded_Consumer functions are used in main:

Reset();

std::cout << "Using SingleThreaded functions to generate digits of PI..." << std::endl;

for (size_t i = FIRST_DIGIT; i <= LAST_DIGIT; i++)

{

SingleThreaded_Producer(i);

SingleThreaded_Consumer(i);

}

std::cout << toPrint << std::endl;

Once implemented, the two functions should look like this:

And if you run the Application, you should have the following output:

At this point, you could insert some MessWithCompiler calls if you want to ensure that this implementation will work no matter what: it is all executed sequentially, so any unpredictable delays will have no effect on the result. You can see for yourself that right now, everything is done on a single thread and sequentially using easy_profiler’s GUI:

![]()

Now that we’ve got our SingleThreaded implementation working, let’s see what happens if we try to do the same exact thing, but this time concurrently with 14 threads, one to Produce and one to Consume a PieceOfPi, per digit. Let’s just copy paste the same code in the NoMutex functions at their appropriate places:

Uh-oh! This time, I didn’t even have to uncomment the MessWithCompiler call to force a data race!:

So what’s going on here? Let’s see if we can get any clues by looking at the results of the profiler (I did introduce an artificial 1 ms extra delay in the functions just so that we could better see what’s going on):

Ah. Without a way to make operations atomic, meaning unable to be interrupted, all of our threads are technically allowed to execute the same code at the same time, all using the same shared resources (buffer, toPrint and iteration). Clearly, this is a critical operation, meaning one that should not be interrupted! In our case, since we’re not protecting our shared resources, we end up with all threads running simultaneously, reading and writing to the shared resources unchecked! This is the equivalent of the “programmers” from our earlier analogy doing things in disorder.

Making Things Atomic

![]() Elmo witnesses the end of the world as we know it

Elmo witnesses the end of the world as we know it

Well, let’s try to remedy to this situation then: let’s use a std::mutex! I’ve already defined a global mutex named m for you, all you have to do is use it in the MutexOnly functions before operating on whatever resources you’re trying to protect. To do so, you have to “lock” the mutex using one of the C++ locks. To know what lock you need to use, here’s a brief introduction of the most useful C++ locks:

- The unique lock is a very generic kind of mutex lock that can be .lock()‘ed and .unlock()‘ed any number of times, though usually you wouldn’t do that yourself, the constructors and destructors of the lock do that for you. You should only use this kind of lock when it is required, for instance when using std::condition_variable’s.

- The lock_guard and it’s successor the scoped_lock do very similar things: they both lock once at construction and unlock once at destruction. This should make them your go-to locks since locking a mutex involves a kernel call, which is relatively expensive. The distinction between the two locks is that the lock_guard is only capable of locking a single mutex at a time (leaving the possibility of a deadlock) whereas a scoped_lock can safely lock multiple mutexes if needed. Between the two, use the scoped_lock unless you need a lock_guard for some legacy reasons.

- Finally, the shared_lock is a very useful type of lock because it does not actually completely immobilise the protected shared resource: a mutex locked by a shared_lock can still be used by other threads as long as all users of the mutex are reading from the protected resource and not modifying it. You can think of the shared_lock as a “read-only lock” if you wish: as long as you’re not modifying anything, locking a shared_lock does not involve an expensive kernel call. Use shared_locks when you only need to read from a shared resource.

The useful thing about mutexes is that as their name indicates, locking them is mutually exclusive: only one thread can ever lock a mutex, and therefore it’s associated resources, at a time, making whatever operations you might perform on these shared resources atomic.

Keep in mind that when using the standard C++ locks, whenever you instanciate a lock it is automatically .lock()’ed unless you specify otherwise, as can be done with unique locks. The opposite is also true, by default, when a lock goes out of scope, it’s destructor unlocks the mutex.

I will not explain those things in depth here, but you should also be aware that not all mutex locking operations are blocking, unique_lock’s and shared_lock’s also have .try_lock() methods (and its variations) which can be used for polling based locking, but you can still end up with a livelock instead of a deadlock if you use these methods.

But what does all of this mean for our code? Well, it means that we’ll be using a scoped_lock in both the Producer and Consumer functions (the consumer modifies buffer and toPrint so we can’t use a shared_lock there unfortunately!):

Let’s run it and see what happens!:

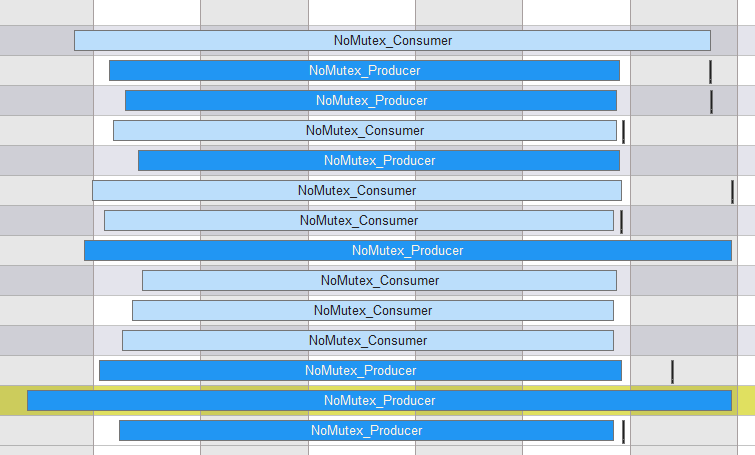

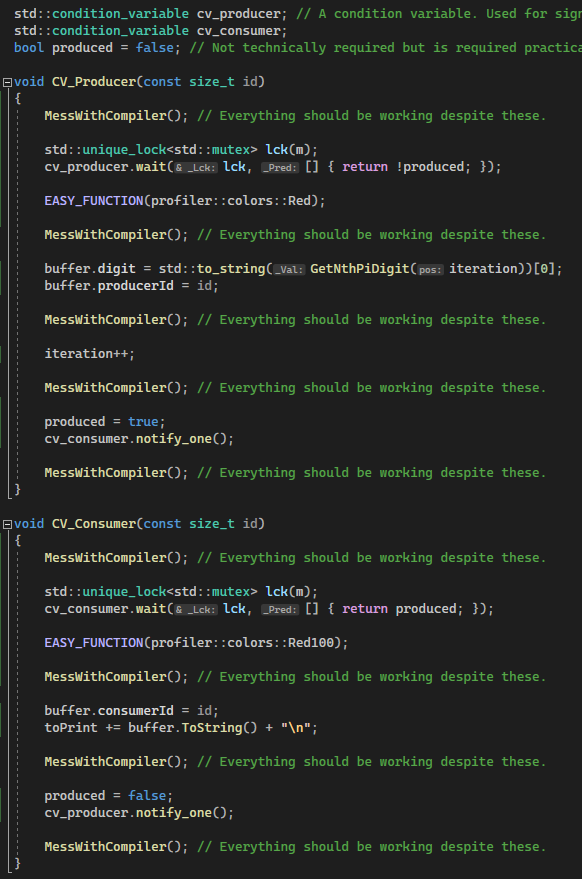

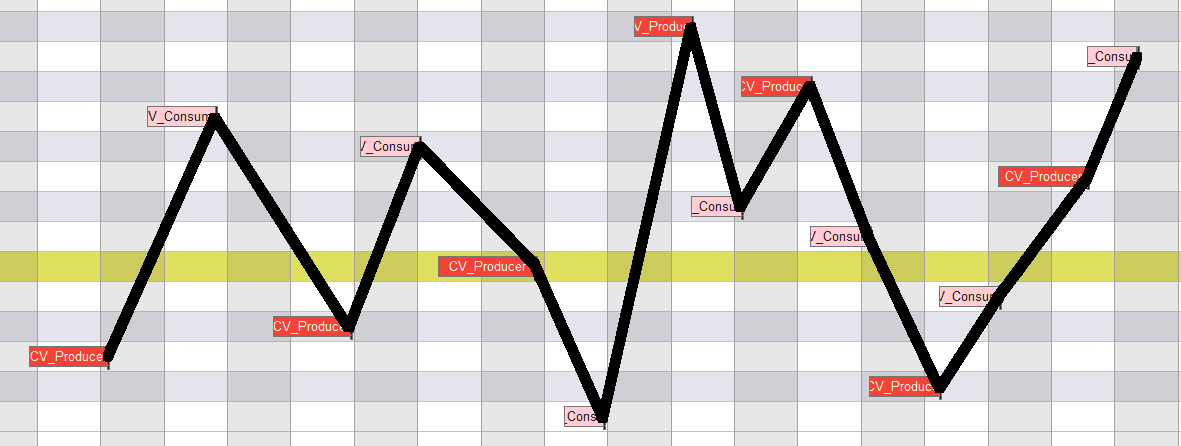

Humm, that’s still not right. Let’s take a look at the outputs of the profiler:

While we did make our operations atomic by using the mutex, the operations are still executed in the wrong order! The very first function to execute is a Consumer, which understandably has nothing to consume, resulting in the “digit: “ output and if you look at the two last functions to get called, they’re both Producers! This is because a mutex has only one effect on the order of operations: it makes the operations sequential, and that is it. For our PI producing and consuming to work we need one more additional tool.

Putting some Order

![]() Evil Kermit telling Kermit to execute Order 66

Evil Kermit telling Kermit to execute Order 66

So, what is our secret weapon that will allow us to organize this unpredictable order of execution into something orderly you might ask? Introducing: the std::condition_variable! A condition_variable is a construct that allows different threads to notify each other that something has happened. A condition_variable works alongside a mutex to put a thread to sleep (a.k.a. block it) but instead of being woken up whenever the locked resource becomes available again, it is woken up upon receiving a notification via the condition_variable.

In C++, you use them like so:

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lck(m); // Mutex is locked in the constructor here.

cv.wait(lck, []{ return somePredicate; }); // Mutex is implicitly unlocked by the compiler here.

// Mutex is implicitly locked again by the complier here.

DoThings();

And some other thread will be responsible for waking up the sleeping thread by calling the following:

cv.notify_one(); // Or cv.notify_all() to wake up every thread .wait()'ing on the cv

Note that while it is technically not required to provide a predicate (some condition to check) to the .wait() method, practically, doing so is mandatory due to spurious wakeups: your thread might wake up unexpectedly when they shouldn’t due to some quirks of the OS, so if they do, providing them with a way to check whether they should actually continue execution or not is pretty much mandatory. Note also that this is pretty much the only case when it’s okay to call .wait() while holding a lock because the condition_variable locks/unlocks the mutex it’s using automatically, doing so in most other situations would result in a deadlock.

We’ll be using two condition_variable’s since we want the Producers to wake up Consumers and vice-versa, if we used only one condtion_variable, we couldn’t specify whether a Producer or a Consumer should be woken up. So with all of this said, this is what the code final working PI producing and consuming code looks like! (despite our best efforts to break it):

And this results in the correct series of digits as we can see:

We can confirm this by looking at the results of the easy_profiler:

There's Always More!

Sharing isn’t always easy, taken from dontgetserious.com, credited to memey.com

Sharing isn’t always easy, taken from dontgetserious.com, credited to memey.com

As much as I would have liked to tell you that this is all you need to know to write good multithreaded code, that’s unfortunately not the case. What I’ve presented here barely scratches the surface of the complexities of making multithreaded programs work but I hope that with these two blogposts you now have the bare essentials to make a multithreaded program and more importantly, that you’ve got now some references you can follow up on to learn more about the subject.

I hope this blogpost has taught you something new and useful and stay curious!