Wéko: My First Experience in the Industry

August 2024 (4613 Words, 26 Minutes)

This blog post is a retrospect on my time at Siro Games sàrl during the development of Wéko: The Mask Gatherer. So, a few introductions are in order. Firstly, Siro Games sàrl is a Geneva-based, Swiss indie game development company.

How it all began.

“Hobbits leaving the shire” by TheTurtlepiggy.

“Hobbits leaving the shire” by TheTurtlepiggy.

I arrived at the company thanks to Lisa Manolache, a talented Game Art classmate I had the pleasure of collaborating with during our last year at school.

At the time, I had been looking for a job for about 5 months without much success: in such a competitive industry, it isn’t easy for juniors to find any position.

Luckily, Lisa had heard from Simon himself, one of the two founders of Siro Games, that they had been looking for “a dev” for the game. More precisely, it turns out that they were looking for a gameplay programming intern, and my profile fit the bill!

So, without much hope, I sent Simon my application, as I had already done to other companies, but this time, things went quickly, and I had an interview. Unlike all the other interviews I had before, this one did not focus on C++ semantics, abstract challenges consisting of reinventing Microsoft Excel, or listing the names of some arcane computer science algorithms. No, for this one, the interviewer asked me something shocking:

“Would you be able to help us with this particular project?”

Wéko: The Mask Gatherer.

The project in question was, of course, Wéko: The Mask Gatherer. Wéko was a project that was in the making for one and a half to two and a half years, depending on where you would consider its start to be.

The genesis of it, according to Simon, was surrounded by what many such good ideas stem from: beer!

Simon tells me of an evening when he and Robin, the other founder of Siro Games, were having a beer and discussing their shared interest in video games. Simon, a data analyst in the banking industry, had some good experience in writing scripts and wrangling with Microsoft Excel. Robin is a very talented jeweler with great 3D sculpting skills. With some alcohol thrown into the mix, it was only natural that the two decided it would be a good idea to make a fully 3D action-adventure game reminiscent of the recent Zelda and Dark Souls games, with no prior experience, funding, connections, or marketing of any sort, all in a canton that barely acknowledges the existence of video games, and in one of the most expensive countries in the world!

And so, make a video game they did. Over the first two years, development went understandably slowly, as Simon and Robin learned the basics of Unreal Engine 4.27, the engine the duo had chosen for the game.

Over time, Simon reduced his hours working at the bank to 50% and used the remaining 150% of his free time (who needs sleep anyways) to work on the project. Eventually, our crazy duo was joined by the very talented Quentin, the music composer of Wéko’s OST, and Rimayé, the VFX wizard responsible for all the flashy and cool visual effects you can find in the game.

There were many others, of course, such as Liam, the cool theater kid who inexplicably figured out how to tweak and create animations for us, and the various people who helped us with translations later on, among others. If you want the full list of people who worked on this game, I encourage you to check out our game’s credits (once you’ve bought it, of course)!

Humble beginnings.

“How it felt arriving on the project” taken from a post from The Irish Times.

“How it felt arriving on the project” taken from a post from The Irish Times.

By the time I had that interview with Simon, most of the core mechanics of the game were already there… kind of. While I did create quite a few mechanics and features from scratch, the majority of my time on the project was spent stabilizing and on rare occasions refactoring the existing code. Simon had experience with scripting, as I mentioned, but he lacked the rigor necessary to create the sizable, reliable game systems needed by this project. When I arrived, while most of the mechanics were present, they would fail to function properly one-third of the time or would consistently fail as soon as they interacted with each other, such as carrying an object and falling off a ledge.

Things were working “well enough” in isolation but would become completely unpredictable or outright game-breaking during the course of normal, multi-hour-spanning play.

And so, when I arrived, a lot of time was spent organizing the existing code, and oh boy, that was NOT an easy task.

As a reminder, the project was now a year and a half worth of action-adventure game code cobbled together just enough to work most of the time, with little to no consideration given to basic good coding practices such as separation of concern or abstraction (worse yet, abstraction that does not actually abstract anything away). If I had needed to get the whole codebase in “proper” order, I would still be working on it today. With the given constraints however, that was simply not doable nor sensible. No, what I needed was to stabilize this castle of cards just enough for it to withstand 95% of the things that the player might throw at it, and the eyes of any programmer be damned!

Thus, my laborious task began. After a couple of game mechanic implementations that we didn’t end up using, I got to work on Weko_BP, the player pawn’s class, the monolith that grouped at least 30% of the game’s code. After much despair, head-scratching, and harassing Simon, who had borne this thing into existence, I organized the player’s code into a finite number of states, like “None,” “Attacking,” “OpeningDoor,” “Dead,” and so forth. With this, tracking down bugs slowly became easier, as we were now able to track the sequences of events that would lead the player to end up with member variables set to incoherent values for the current context of the game… most of the time.

Again, in all I did, I had to make careful consideration of what needed to be refactored and what was too fragile and intertwined with everything else to hope to rework within a reasonable amount of time. Where I couldn’t rewrite things, either because that would take too much time or because I simply couldn’t understand all the myriad of effects changing a single value would cascade into, I did my best to add failsafes, write sanity checks, and if all else failed, just comment everything for the next time my bug hunt would lead me to that particular piece of code.

After a few months of this, with Weko_BP as well as other similarly convoluted areas of the codebase, I was finally starting to get the big picture of what was happening in the game at any given moment… for most of the systems, anyway.

Facing the monsters.

“Scene from Young Frankenstein”, 1974 by Mel Brooks.

“Scene from Young Frankenstein”, 1974 by Mel Brooks.

While most of the systems I’ve had to work on were fairly straightforward once I poked around them for a while, some of them are still bordering on dark magic to this day. One of these major systems was the game’s save system.

I had arrived on the project right when Simon was implementing a saving mechanic into the game, and that was namely one of the reasons he needed a programmer.

Simon had followed the tutorials of a YouTuber called Reid (I unfortunately can’t find the exact name anymore) and implemented a C++ save system in the project… but he didn’t understand C++. So, of course, once things were inevitably broken, he was unable to fix the code to make it work for the project. Instead, for the parts that were broken, Simon ended up making a second save system, on the Blueprint side of the engine, just for those last bits of data that needed to be saved.

That is when I arrived on the project, and after a few months, I needed to stabilize these systems, as well as add some more functionalities to it. Namely, along with the player’s stats and the world’s states, we needed to be able to save the player’s progress and upgrades, and the player start that was to be used to respawn.

Just like every other system in the project, its usage was chaotic and spread across 50 or so classes. This task turned out to be very much a “Weko-ism” as I call these now on: it worked 75% of the time, it was a pain in the bum to extend it, and following any changes to it, a lot of playtesting would be needed to ensure everything is STILL working as intended. It was either that, or a month or so of code rewrite, which at such a small scale of a team was not justifiable.

Unlike Blueprint systems, errors on the C++ side of an Unreal project usually end up in crashes, and it took a lot of trial and error, as well as guesswork, to iron out all of the crashes and save corruptions linked to the C++ side of the save system. And so, after a few initial weeks of work on it, followed by a lot more debugging for the remainder of the project, this system was stable enough to be released with.

Another such “Weko-ism” of the project has been the inventory system. The game, being an RPG, obviously has a lot of items. Some of them you can equip, some you cannot, some you can give to NPCs, others you keep for the whole game. Therefore, one of the main systems in the game is the player’s inventory. The player can move or equip items around by drag and dropping things with a mouse, double-clicking, or by using gamepad buttons. It goes without saying that this mechanic is spread across ~20 or so classes, Weko_BP being one of them. While making the save system work with the inventory was a challenge in itself, the real troublemaker of the system turned out to be Unreal Engine itself.

The engine has two ways to handle input, as far as I can tell: the Unreal Engine mode, referred to as “Game” input mode, and Slate’s input handling. Slate is a third-party UI framework upon which Unreal’s UMG interface is built.

It’s hard for me to say whose fault that is, but while Unreal provides a nice and unified way of managing player input, with priorities, generalization of input hardware, and so forth, this is not the case with UMG. In Unreal, input seems to be processed in two very different manners, and for our use case, in two mutually exclusive manners. While Unreal does have a “Game and UI” input mode, we weren’t able to use it with our player pawn, and so the player’s input had to be very carefully managed in a game of input responsibility passing, lest the game would end up in a state where user input is being ignored by both handlers of inputs (game side and UI side).

Add to that the fact that the passage of time is handled differently by UMG and Unreal’s Actors, the idea of implementing the ability to pause into the game has long scared us, until at last, following player feedback, we managed to hack something together.

The most frustrating and bug-prone part of the inventory’s code was the fact that the game supports both a keyboard and mouse control scheme and gamepad controller schemes. On the Actor side of things, this distinction is very minor, Unreal making a great generalization of inputs. On UMG’s side, however, things are very different. Unlike regular inputs, inputs for UMG had to be hard-coded into the ~20 or so classes, and so, any iteration of the control scheme for the game would often result in needing to manually change those bindings, which was both time-consuming and error-prone.

And lastly, with the gamepad control schemes especially, a lot of care needed to be given to “focus” passing. In UMG, only the currently “focused” widget receives inputs from the player, unlike with Unreal’s Actors, and so if the focus is lost, one way or the other, with a gamepad, that would essentially imply a softlock of the game. And of course, UMG does not provide a function to retrieve the currently focused widget to help the matters.

However, after much headache and a lot of lessons learned for the next project, that too, was stabilized. Not perfect by any stretch of the imagination, in fact, you can still perceive some oddities with the game’s UI today if you pay good attention to it, but these oddities aside, the player is able to interact with the inventory and all of the related UI systems without bothersome bugs.

And creating my own monsters.

“Another scene from Young Frankenstein”, 1974 by Mel Brooks.

“Another scene from Young Frankenstein”, 1974 by Mel Brooks.

What happens when you give an inexperienced, fresh-out-of-school programmer the responsibility of a new, major feature in a game? That was the situation I had found myself in during the summer of 2023: the game finally was able to justify implementing bosses in the gameplay!

Initially, 6 bosses were planned (just a small number for a small team, just small enough to handle while also developing the rest of the 6+ hours of an RPG’s gameplay, of course), and so, the good programming student that I was, I immediately saw this as an opportunity to finally implement a nice, well-designed, reusable, and expandable system, the way a true programmer would!

At the time, we were also reworking the code of enemies of the game, and so, I saw this as an opportunity to harmonize things, take what already exists on the MasterEnemy_BP side of things, generalize it and build a system able to be used for bosses and regular enemies alike.

And, it went exactly as you would expect.

Luckily, with the time pressure and basic self-awareness, I did not spend weeks figuring out the best design for the task at hand, and I say luckily because as both the bosses and enemies would be iterated on, it became very clear that there was no way I would have been able to account for all of the requirements that such a system would entail with the little experience I had.

Instead, the task ended up being an initial 2 months of development followed by regular tweaking for the rest of the time until release.

First, we started with the Golem Boss: a big stone giant that is invulnerable to any kind of attacks until he rushes into spiked pillars and stuns himself. Just like enemies, he is able to attack in melee… and that’s where the similarities with the main enemy class end. Seeing the difficulty of abstracting two kinds of enemies that have very different behaviors and characteristics made me quickly realize that it was best to handle bosses and regular enemies with two separate bits of code.

That did not stop me from trying to regroup most of the functionalities of all bosses into a single base boss class, however. It took a lot of overriding, expanding, and conditional execution, but the game does have a base boss class that is responsible for a good chunk of the logic of the bosses… but looking back at it, that was not a good idea.

For regular enemies, ones you will be seeing constantly, in many different variations, it’s great to have a base class with Actor Components used to define some specifics, but for bosses, a common base class is a hindrance.

Such rigidity restrains creativity and most of the time, due to the very varied nature of game boss design, you just end up making hacks upon hacks to make specific mechanics work, all the while taking care not to break the general logic that is being used by all the other bosses.

In the end, the game only has 4 bosses (which is still a lot more than I would have expected), but I reckon that 6 bosses would have genuinely been possible if we had taken the decision to re-implement each boss from scratch rather than ensuring that the most amount of code was able to be reused across bosses.

This is a good example of one of the lessons I’ve learned in the making of this game: “The better is the enemy of the good (enough).” At school, we are understandably taught good programming practices and are taught the basics of good software design, but in reality, in small teams anyways and without much experience, the reality is that it’s very difficult to justify “proper code” over “working code.” I’m sure the situation is very different with a bigger team, of course.

A screen capture of the Cinos fight by CrankyTemplar.

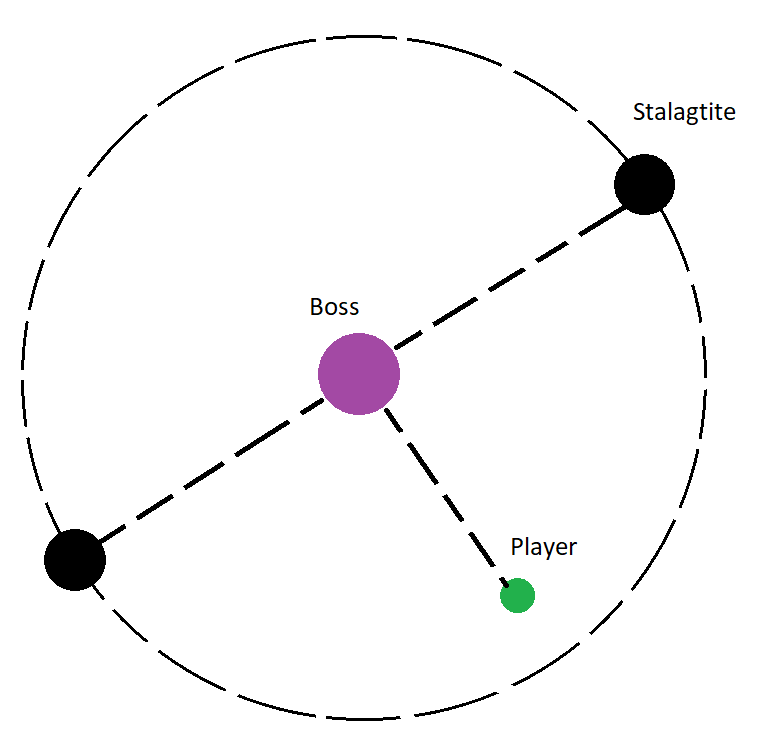

As an example of this, consider the following mechanic from our game: the boss jumps in the middle of the room and prepares to fire a big, one-shot-kill laser that sweeps the whole room, but conveniently also drops down two stalactites on either side of him that allow the player to survive the attack if they hide behind them. One problem that very quickly became obvious was that if the location of those two stalactites was left up to random chance, the player would often end up being hit by the falling stalactite and then swiftly killed by the laser as they get up.

To fix that, it would be best to ensure that the two stalactites consistently spawn on either side of the boss on a line that is perpendicular to that formed by the position of the boss and the player: this way, the player doesn’t get squished by the thing that is supposed to protect them and the two stalactites are always within a reasonable distance from the player to ensure that they can reach them on time.

A top down view sketch of the ideal placement of the stalagtites.

A top down view sketch of the ideal placement of the stalagtites.

Now, what would be the proper way of computing the location of the two stalactites? Surely you’d need to use trigonometry and geometry to find these locations, take into account the rotation of the boss pawn, the direction of the player, and so on and so forth.

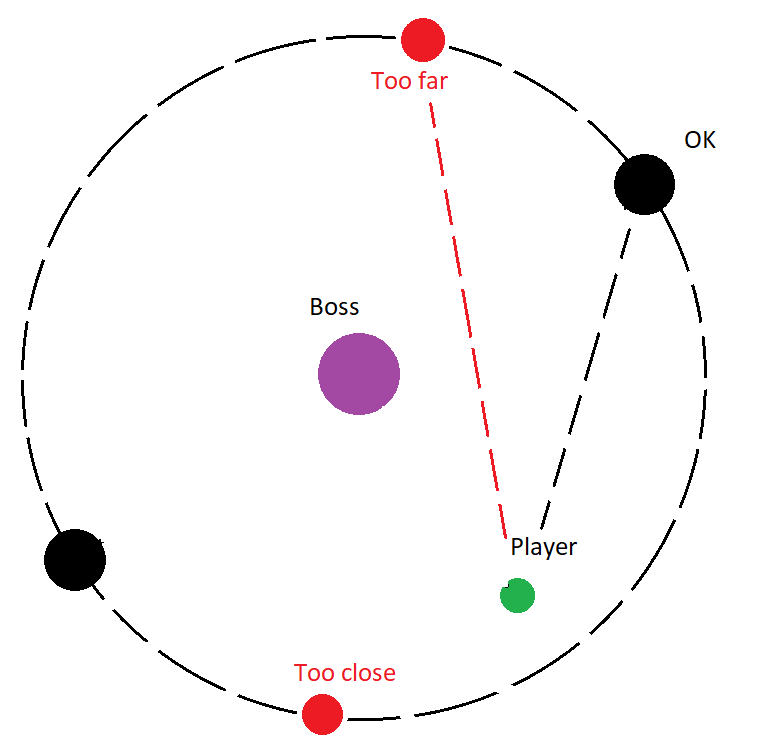

Or… how about we just generate one random position on a circle around the boss and check that it’s not too close to the player? And if it is, eh, just generate another one. Then use that position to spawn one stalactite and compute the other position for the second stalactite on the other side of the boss, easy!

What’s that? The player still gets hit by the second stalactite because the first one has spawned behind the boss, relative to the player? Well, just check that the distance of the first stalactite is neither too large nor too small, and tada! You get stalactites that spawn on either side of the boss consistently and that do not crush the player when they appear.

Example of a rejected set of position marked in red and a valid set of positions marked in black.

Example of a rejected set of position marked in red and a valid set of positions marked in black.

Now, when I described this solution to a junior classmate of mine, he very understandably facepalmed upon hearing that nonsense. Leaving the generation of a stalagtite position up to a random number generator that might fail to generate an appropriate position multiple times in a row after all, there even is technically speaking a chance of the program getting stuck in an infinite loop due to failing to generate appropriate positions! Inconcievable!

But… that is currently how the stalactites of Cinos, the third boss of the game, spawn. Why? Because it works. Consistently too.

And unlike with the “proper” approach to the problem, I did not have to sketch out and formulate it as a math problem, which is a good thing because that is not one of my strengths.

Mind you, that does not at all mean that I couldn’t figure out the proper way to solve that problem, just that it would have taken me more time than this approach. But for what? To feel satisfied?

No, that time was much better spent debugging the rest of the game and implementing the rest of the mechanics. I am the only person who has had to touch that particular bit of code and it wasn’t a feature that has been reused anywhere else, nor was this solution a weight on the performance of the game, it is just unsightly. But that, I guess, is how you make a small Zelda-like adventure game with only 5 people that has a playtime of over 6 hours.

A pawn in the greater scheme of things.

“A happy programmer” taken from an article by Maker’s Aid.

“A happy programmer” taken from an article by Maker’s Aid.

With this first industry experience, it was the first time that I occupied an important position in a project without having a major say in it. Up until then, for group projects, I had usually taken a leadership role, but arriving in this project halfway in, I, of course, assumed a more passive role.

Not that my input wasn’t valued mind you; quite the contrary, I’ve never felt like my suggestions or ideas were discarded nor did I ever feel like my inputs failed to improve the game design on the aspects I had found weak, but having had some limited experience in making sure a project arrives at its term, it was a nice change to not have to worry about anything other than programming. This has really made me appreciate the invisible work that Simon and Robin have done during the time I was able to just focus on programming.

Up until now, you might think that I’ve been throwing Simon under the bus, criticizing his old code, but that is very far from it. Seeing what Simon was able to accomplish alone, programming-wise, is quite impressive considering the scope of the project. Of course, someone without a formal software design education would make mistakes, and for all the grief I’ve given him here, I absolutely cannot guarantee that I would be able to make a “proper” project. Programming-wise, I am a junior with only a little theoretical knowledge in software design, after all.

Where I really have to give credit to Simon is pretty much everywhere else.

It is very hard to get a project going from the ground up when there isn’t yet a framework set up you can rely on. It is also hard to narrow down such a large-scoped genre of games into something that is doable for a small team like ours. It is very hard to find a budget for a game of this scale, even more so in Switzerland where salaries are high. It is hard to market a game of a new IP without prior experience and with a limited budget. It is hard to set up a new company with all of the administrative work that this entails. It is hard to find reliable contacts in the industry when you have not already spent years in it. It is hard to keep up the morale of your coworkers and to ensure that the project keeps on advancing at a steady pace despite all of the difficulties. It is hard to stay motivated yourself with all of this pressure on your shoulders.

Yet all of those things, Simon accomplished. I cannot express the respect I have for him and Robin for pulling all of this off. They very much are an inspiration and a striking example of the kind of mental strength it takes to create a game studio in the current industry. I am genuinely honored to have been able to work beside them.

The bugs.

“Heimlich versus a programmer” from A Bug’s Life.

“Heimlich versus a programmer” from A Bug’s Life.

We, players of modern games are sadly accustomed to games launching as buggy messes, especially coming from certain AAA studios that shall remain unnamed. Up until the release of Weko, bugs were my greatest concern for our game. If these huge studios, with dedicated QA teams, talented programmers, and decades of experience, are consistently releasing games that are filled with game-breaking bugs at release, how could our small, inexperienced studio hope to do better?

All throughout the development of the game, I had the fear that upon release, despite our best efforts, our game would suffer from bad reviews at launch due to bugs, a decisive time for the success of the game. And yet, at release, despite our relatively complex gameplay, an inexperienced programmer (let’s be honnest), and an absence of a proper QA team, the game turned out to have very few bugs. There were some, yes, but none that were game-breaking and affecting large amounts of players.

This had been quite a shock to me. I knew the questionable design of the code, and yet, with only regular playtesting and the help of some generous fans who accepted to playtest the game for us regularly before release, we were able to have a release so stable that not a single Steam review made in the first month of the release mentioned any bugs.

How could that be? Maybe we just got lucky. But perhaps what is being told on the consumer side of the video game community has some truth to it: that quality is being laid to the wayside in exchange for profits by certain studios. If a tiny studio like ours is capable of achieving a reasonably bug-free release with a game that is not inherently simple, it is frankly quite hard to defend those AAA studios that have all the budget, experience, and infrastructure to do better yet still choose to cut corners there.

To put a bow on things.

“View of a maze” taken from Wallup.net.

“View of a maze” taken from Wallup.net.

In summary, this first experience certainly didn’t go the way I expected it to.

Coming out of school, I expected to be brought into a big team with seniors to teach me the ropes of some very technical subjects. Instead, I had joined a small team where I ended up being the most knowledgeable programmer as a junior and spent the overwhelming part of my time in Unreal’s Blueprints instead of C++.

I had expected to be required to write very well-structured and designed code that respected all the best coding practices, but instead, I’ve rarely ever spent time designing systems and much more time hacking the existing codebase into something that would just get the job done without resulting in bugs for the player.

I had expected to have to release a game that was potentially hindered by bugs and perhaps an incomplete one due to scope creep; yet instead, we’ve released a very stable game that flows very well and feels complete.

It is difficult to put into words all that I have learned, and perhaps I did not have a typical learning experience for a junior gameplay programmer, but today I do feel much more confident in my abilities. There will undoubtedly be people much more talented than I am in the technical aspects of game programming, but facing all of the peculiar challenges I’ve had to see for the development of this game has certainly left me much more resourceful.

I may not know the pseudocode for detecting cycles in a directed graph by heart, but I do now realize that there are a myriad of possible solutions to a single problem. And if there isn’t one, there’s at the very least dozens of alternative ways to pivot around a challenge to end up in front of a problem to which you do have a solution.

That, I think, is the most valuable lesson I’ve got out of this first experience in the video game industry.